Regardless of personal views, it has grown near impossible not to take notice of non-fungible tokens (NFT). Even with recent slowdowns, total NFT sales volume could top $90 billion by the end of this year (after seeing a record $40 billion in 2021). That success has brought a new type of interest from a new group of participants in the NFT ecosystem – lenders.

And with a new participant in the NFT space comes a new label for NFTs – collateral.

Whether it is an NFT-secured loan, a used car loan or a multimillion-dollar leveraged finance of an entire company, the motivations of lenders and borrowers are consistent. The lender is incentivized to give temporary funds to the borrower in exchange for an interest rate charged on top of the principal loan amount. The borrower is willing to pay the interest rate because they need an immediate source of liquid funds without selling the asset.

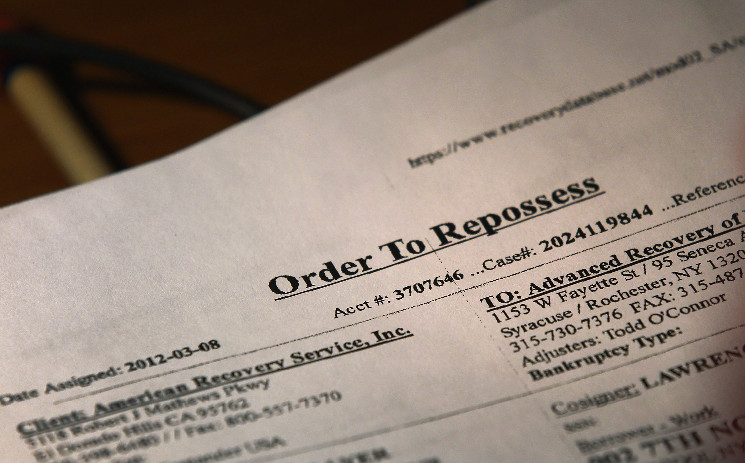

What does change in each asset class is how the lender is protected from a borrower’s non-payment of the loan, or “default.” In a used-car marketplace, the lender receives ownership of the car if the borrower defaults. A deep foundation of secured lending regulations (primarily Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code, or UCC) gives lenders the necessary confidence that this car ownership transfer will occur with or without the defaulting borrower’s cooperation.

So what secured lending regulations apply to NFTs?

Jeff Karas is an attorney at the law firm of Anderson Kill. This article is excerpted from The Node, CoinDesk's daily roundup of the most pivotal stories in blockchain and crypto news. You can subscribe to get the full newsletter here.

While simple in theory, and even in smart contract execution (if borrower does not pay, then the NFT transfers from borrower wallet to lender wallet), the legal protections of using an NFT as collateral is a complicated question of “perfection” of the lender’s security interest. An NFT is not a car, and under the current UCC regulations an NFT is not even “art.” It is most likely either a “general intangible,” which is effectively the UCC’s overflow bucket most commonly used for difficult to categorize collateral, or it is an “investment property,” which is a term encompassing securities and other security-like financial assets.

If an NFT is a general intangible, then the lender’s simplest path to perfection is via the filing of a UCC-1 Financing Statement in the state where the NFT owner is deemed to be located. Knowing a car owner’s legal name and location may be simple, but in the digitally native and often intentionally anonymous world of NFTs, a lender may find it difficult to know the precise filing jurisdiction to perfect their interest in a Bored Ape owned by “MoonBoiBallz99.” This hurdle makes perfection by filing of a UCC-1 an impractical solution at best, and a fool’s errand at worst.

Perfection of an NFT labeled as investment property may be more appropriate for crypto focused lenders and borrowers. A security interest in an investment property is perfected by “control.” A lender can obtain control under the UCC if (1) the NFT is deposited directly into the lender’s wallet, which may be uncomfortable for the borrower, or (2) the NFT is transferred to a third party and an agreement is signed by the lender, the borrower and the third party. Under this tripartite agreement, the borrower grants a lender the security interest in the NFT, but the NFT is held in a specific account (or wallet) with the third party. That third party, in turn, agrees to only follow the directions of the lender, thereby giving the lender “control” of the NFT, perfecting their security interest.

Three-party agreements of this flavor, often called an “account control agreement,” are common in traditional lending ecosystems where the third party is a bank or bank-like entity. However, banks are more often labeled as the “enemy” than anyone’s trusted middleman in the cryptocurrency and NFT space, so any legitimization of NFT lending will require new projects to fill this void.

Several teams have already dipped their toes into the NFT lending waters with assorted models of execution and widely varying levels of real and perceived legal protections at their core. The most used example to date is the South African project NFTfi, which has facilitated nearly 13,000 loans and a total cumulative loan volume of over $212 million since its inception (according to statistics available from Dune Analytics). NFTfi’s agreements between the borrower and lender are based entirely on smart contracts “signed” by each party, but it is unclear at an initial glance how tight those contracts are from a legal protection perspective. No plain language agreements are presented to any lender or borrower on the NFTfi system, but it is reported that over 20% of all loans are defaulted on and there have been no publicized failures in the transfer of the collateralized NFT upon any borrower’s default.

Other NFT lending platforms have started to pop up in recent months (including Arcade, which completed a $15 million Series A funding round in December led by Pantera Capital). More are on the way. Some are primarily on-chain services like NFTfi, while others, like Nexo.io, are promising a more nuanced, over-the-counter approach (including a formal application process for each borrower). Whatever the method, it is unclear how much any of these new platforms will focus on the legal enforceability of their lending agreements.

It is possible that, as in many marketplaces, there will not be a call for any strenuous legal protections until there is an issue worth disputing or an issue big enough to make headlines. When that time comes, crypto and secured lending attorneys should be ready to pick up their old copy of the UCC and understand the unique crossroads blockchain has brought to the space (again).

coindesk.com

coindesk.com