EtherRock Price is a Twitter bot account that tracks the price of EtherRock, a collection of 100 pet rock JPEGs that live on a blockchain. Spun up on Aug. 6, the automated Twitter account arguably has more utility than the project it serves. It’s a direct line into how people are valuing a series of worthless-on-the-surface non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Created in 2017, EtherRock is one of the oldest $NFT projects, but it has only recently attracted buyers’ attention. Currently, the cheapest rock, Rock ID 96, is listed for 678.88 $ETH, or about $2.2 million. The owner of Rock 0 is asking for 10,000 $ETH.

By its founder’s own admission: “These virtual rocks serve NO PURPOSE beyond being able to be [bought] and sold, and giving you a strong sense of pride in being an owner of 1 of the only 100 rocks in the game :)” Indeed, apart from rank and small variations in color, all the rocks are identical reproductions of the same royalty-free, clip art image.

In a sense, EtherRock is the quintessential contemporary $NFT project: The humor, the rabid fan base, the self-aware, total conflation of value and price. No one can say for sure why a rock that sold for $50,000 at the beginning of the month is now worth millions – other than there’s momentum behind these boulders.

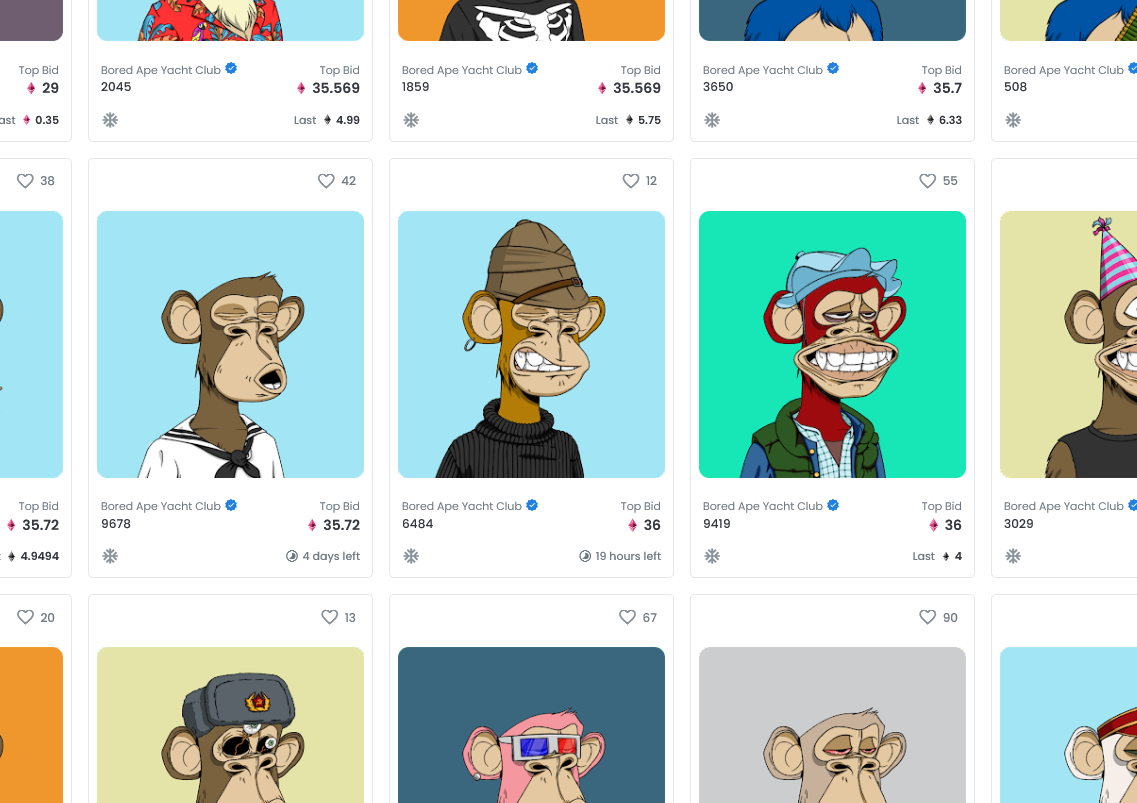

Nowhere is that more evident than in the project’s closely watched “price floor.” A term borrowed and bastardized from commodities trading, a floor price is the lowest price at which an $NFT can be bought for a particular project.

In commodities trading, the term refers to price controls imposed by governments or groups that set the minimum amount someone could charge for a good, commodity or service. It functions as a way to prevent a race to the bottom in pricing, often to buoy a particular industry.

In crypto, it’s often one of the few hard pieces of data that accompanies an $NFT project, and is somewhat comparable with bids and asks in traditional order book markets. But it also may not say much about the viability of a project.

In semi-liquid $NFT markets, a hot project will have a rising price floor. But given the limited number of buyers and sellers on both sides of a unique digital asset trade, there’s no guarantee the price can hold.

“A lot of this stuff just gets bid up very hard by speculators. But then there isn’t necessarily liquidity on both ends,” an $NFT trader who goes by 0xSisyphus said in an interview.

Like with all else in crypto, there’s also a social meaning behind the numbers. A price floor also represents the weakest hands in a market – the lowest price at which a particular seller is willing to undercut other holders. In some communities, people are badgered into not selling at a given price.

Of course, price floors are not the only way to judge the value of an $NFT. There are subjective readings of a project’s community, there’s an asset’s programmable rarity, there’s provenance and history. There’s also more technical metrics like determining what percentage of a project’s supply has been listed over time – a cue into how many motivated sellers there may be.

Crypto is not unfamiliar with industry-specific ways to measure novel digital assets, which often do more harm than good. Take market capitalization: Derived by multiplying the total amount of coins in circulation by a cryptocurrency’s price, the metric is essentially meaningless as a way to judge different assets with different circulating supplies. There’s also “total value locked,” or TVL. Specific to the decentralized finance (DeFi) industry, this is a metric former CoinDesk reporter Brady Dale called “so simple it’s confusing.”

Given the absurdity of the moment – when the ground floor for getting into digital rocks is an astronomical $2.2 million – it’s not surprising that people are latching onto any metric they can.

coindesk.com

coindesk.com