A reminder, dear reader: If you're accused of committing massive fraud and risk facing the rest of your life in prison, you should probably turn down that interview with "Good Morning America."

Such advice might've served Sam Bankman-Fried, the disgraced crypto founder who couldn't keep quiet last year following the collapse of his FTX crypto empire, after he allegedly stole billions of dollars of customers' money.

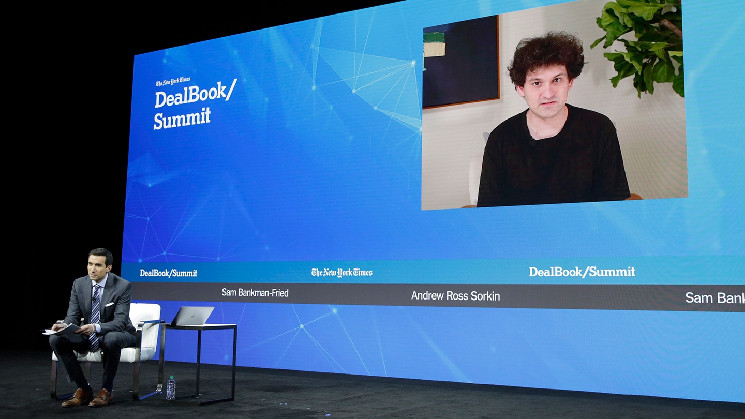

To the chagrin of his lawyers (Asked by journalist Aaron Ross Sorkin on Nov. 30 if his attorneys were "suggesting this is a good idea for you to be speaking," he replied: "No, they're very much not."), the crypto founder went on a media blitz following FTX's collapse – seemingly desperate to dish out his side of the story to practically anyone who would listen, be they journalists, Twitter personalities or vexed crypto day traders.

Bankman-Fried was asked during his direct questioning last week why he spoke to so many journalists. "I felt like it was the right thing for me to do," he told his lawyer.

Right or wrong, the FTX founder's media strategy seemed as perplexing as ever on Monday, when prosecutors spent hours peppering him with questions about potential criminality at FTX — using his countless post-collapse interviews as corroborating evidence.

The bulk of Bankman-Fried's exchanges with Danielle Sassoon, the assistant U.S. attorney who led the questioning, followed a strikingly similar pattern. Sassoon would ask the defendant a question: "In private, you said things like 'f–k regulators, didn't you?" Bankman-Fried would respond to the effect of "I don't recall saying that," or in the case of the comment disparaging regulators: "I said that once."

Then, whether or not Bankman-Fried could remember making a statement, Sassoon was always ready with corroborating evidence – like the defendant's ill-advised, viral text exchange with a Vox reporter expressing his distaste for regulators.

SBF's friendliness with journalists

Bankman-Fried's proclivity for speaking with the press had worked well for him historically. His trademark curly mop of hair, T-shirt and cargo shorts were complemented by a nerdily irreverent speaking style that lent him an air of earnest eccentricity in interviews.

This public image was beamed around the world by his frequent media appearances, which may have played a key role in helping him woo users and investors to FTX. Bankman-Fried acknowledged as much during his trial, confessing that he became the public face of FTX by happenstance after it became clear that he had a knack for press.

In the lead-up to Bankman-Fried's cross-examination this week, prosecutors have scrutinized his policy of customarily deleting written communications – a practice he testified to picking up during his time as a quantitative trader at Jane Street, where junior employees were advised to consider the "New York Times Test."

"Anything that you write down," he recalled during his direct questioning last week, "there's some chance it could end up on the front page of The New York Times." He added: "A lot of innocuous things can seem pretty bad" without context.

Bankman-Fried had an odd interpretation of this rule. While he set most internal FTX chats to "auto-delete" — apparently to prevent them from showing up in The New York Times — he often spilled his secrets directly to the Times and other news outlets. The results of these post-collapse conversations, when presented in a courtroom, still looked "pretty bad."

Sassoon's grilling excerpted interviews with Sorkin of The New York Times, George Stephanopoulos of "Good Morning America" and Bloomberg's Zeke Faux, among others – just a handful of the journalists Bankman-Fried spoke to immediately after FTX's fall.

At least five journalists whose names showed up in pieces of evidence pulled up for the jury Monday were physically present at the Manhattan courthouse.

Although he left prosecutors with a sparse written record of his conversations at FTX, his press appearances after FTX collapsed, wherein he walked step-by-step through the fall, contained more than enough material for Sassoon to puncture his credibility, and to rip apart the sympathetic image he painstakingly constructed for himself in early media interviews and hours of direct questioning from his own lawyers.

Another inconvenient interview

A key moment in Monday's cross-examination revolved around the allegation that Alameda Research, a trading firm Bankman-Fried founded before starting FTX, had "special privileges" on the exchange that allowed it to steal billions of dollars in user deposits.

Bankman-Fried has generally been evasive when asked if Alameda had special privileges on FTX, since admitting that would be a huge boon to the government's case against him.

"Isn't it true that as CEO of FTX you were aware that Alameda had more leeway than other traders on the exchange?" Sassoon asked him at one point on Monday. Initially, he pushed back: "Not in those words specifically, and I don't know what context it was in."

With some prodding from Judge Lewis Kaplan, Bankman-Fried conceded that Alameda had "put on a far larger position than I had anticipated" but he said it was due to a banking relationship between Alameda and FTX that he maintains was kosher. He made no mention of any Alameda special privileges or extra "leeway."

Sassoon drilled further: Alameda's large position "was also the result of the margin rules that did not apply to Alameda, correct?"

"I'm not sure that's how I see it, no," Bankman-Fried responded.

Sassoon, unphased, moved right ahead with her questioning. She pulled up an interview between Bankman-Fried and Bloomberg's Faux. The article was dated December 2022, a few weeks after FTX fell apart: "When I ask if Alameda had to follow the same margin rules as other traders, he admits the fund did not," Faux wrote. "'There was more leeway,' Bankman-Fried says."

Although most of his internal communications have been deleted – perhaps a wise move depending upon what they contained – a remarkable amount of the prosecution's evidence was drawn from media appearances like this one that Bankman-Fried did after he stepped down from his role at FTX. Had he stayed quiet – adopting some variant of the New York Times Test to avoid letting his words come back to haunt him in court – one imagines this portion of the case could have taken a strikingly different course.

coindesk.com

coindesk.com