In an interview with CoinDesk, Don Wilson slams the SEC's crypto crackdown, drawing parallels to his past victory over the CFTC, another Gary Gensler-led regulatory agency

The SEC's stance toward crypto "reminds me of 'Atlas Shrugged,'" Wilson said. "[If] everybody is breaking the law, they get to selectively harass whoever they want to."

Wilson thinks the SEC's lack of clarity for crypto companies is intentional, not accidental.

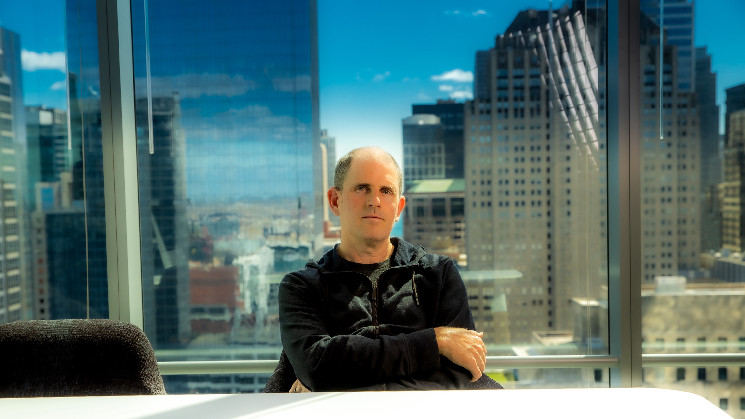

Don Wilson is feeling déjà vu.

This month, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission sued Cumberland DRW, a division of DRW, the Chicago-based trading giant Wilson founded and runs. The markets regulator accused the company of trading at least $2 billion of cryptocurrencies including Solana's SOL and Polygon's POL (formerly MATIC) without first getting permission. The case hinges on the SEC deeming those assets securities, a designation that imposes all sorts of requirements on traders like DRW.

It's not DRW's first tangle with a regulator. In fact, it's not even DRW's first tangle with Gary Gensler, the SEC's chairman.

Back in 2013, when Gensler ran the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the agency filed suit against DRW and Wilson himself, claiming that they manipulated the market for an obscure interest-rate swap. Wilson and his firm denied any wrongdoing – they had, they argued, simply discovered a lucrative arbitrage opportunity their competitors overlooked.

They fought the CFTC and won – big time.

The judge in the case, District Judge Richard Sullivan of the Southern District of New York (now a judge in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit) emphatically sided with Wilson after a four-day bench trial, slapping down the CFTC's suit in a scathing 2018 dismissal. He called the CFTC's arguments "absurd."

Wilson recalls that ruling fondly.

'Earth is flat'

In an interview with CoinDesk on Friday, Wilson said his favorite lines in the dismissal were Sullivan's quip that "it is not illegal to be smarter than your counterparty in a swap transaction" and the judge's assertion that "it is only the CFTC's Enforcement Division that has persisted in its cry of market manipulation, based on little more than an 'Earth is flat'-style conviction."

Gensler had long since left the CFTC by the time Sullivan smacked down the regulator's case. But he was there to launch it.

"It seemed to us that what the CFTC was trying to do was expand the definition of manipulation," Wilson said.

That line probably sounds uncomfortably familiar to crypto insiders.

Under Gensler's leadership, the SEC has taken steps, both official and unofficial, to expand its authority over crypto. In February, it broadened the definition of a securities "dealer" to capture a large swath of the crypto market, which fits with Genser's often-repeated belief that "the vast majority" of crypto tokens are securities and thus deserve SEC oversight.

Read more: Gary Gensler: The Crypto Lightning Rod Who Runs the SEC

Gensler has said over and over that crypto businesses simply need to "come in and register," and they'll be able to trade crypto without issue. The Oct. 10 lawsuit against DRW says: "Cumberland bought and sold, for its own accounts as part of its regular business, at least $2 billion worth of crypto assets that were offered and sold as securities. In doing so, Cumberland acted as a securities dealer but failed to register as a securities dealer with the Commission."

Wilson sees it very differently.

"We set up a broker-dealer and tried to register it to trade crypto assets," Wilson said in the interview. "The markets division of the SEC said, 'If you register, the only ones you could trade are ETH and bitcoin.' The enforcement arm said, 'You failed to register.' Obviously, those two things are inconsistent."

The SEC did not respond to CoinDesk's request for comment.

Bringing 'Atlas Shrugged' to life?

Kevin Haeberle, a professor of corporate law and securities law at U.C. Irvine School of Law, said that some heads of regulatory agencies are simply "more aggressive" than others.

"When those individuals find themselves limited in what they can do in terms of rule-making, they often turn to regulation by enforcement," Haeberle said. "The SEC has a history of using the broker-dealer definition in a broad manner in order to ensure that customer-protection laws apply in a situation where the SEC would like them to apply – even where it isn't clear that the entities at issue are in fact acting as broker-dealers."

To Wilson, there are many similarities between the SEC's enforcement actions under Gensler and the enforcement action he faced from the Gensler-led CFTC.

He has a theory about why. In Wilson's view, the lack of regulatory clarity from the SEC is a feature, not a bug, of Gensler's leadership at both agencies. Without establishing clear rules or guidance, and demurring when asked whether a given token might be a security, the SEC preserves its ability to selectively prosecute, Wilson said.

"This dynamic put the SEC in a position where they could say everyone is breaking the rule, and we're just going to go after whoever we want to. [It] reminds me of 'Atlas Shrugged,'" Wilson said. "[If] everybody is breaking the law, they get to selectively harass whoever they want to."

Wilson's theory is not outside the realm of possibility. James Fanto, a professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School and co-director of the school's Center for the Study of Business Law and Regulation, told CoinDesk it's "absolutely" possible that Gensler's SEC is being purposely vague in order to preserve its power.

"That's sort of the typical enforcement approach," Fanto said. "They don't gain from being crystal clear on things, especially in a new area."

And what does the SEC stand to gain from its opacity towards crypto? Fanto said it could be a few things.

"Some of it's money, some of it's just to get the publicity and attention," Fanto said. "Probably some of it is just this space that's not regulated, and 'Someone's got to do it, [so] we're going to do it.' But this is an SEC, under [the Biden] Administration, that has been very, very activist in an enforcement-driven way on everything, and not just crypto – on everything."

It's not just Wilson who's frustrated with the situation. Last month, Rep. Patrick McHenry (R-N.C.) called the SEC a "rogue agency." SEC Commissioner Mark Uyeda recently called Gensler's tenure a "disaster for the whole [crypto] industry."

Gensler, for his part, has emphatically denied accusations that his agency hasn't established clear regulations. He frequently points to a 2017 report from the agency (before he joined it in 2021) concluding that tokens issued by a decentralized autonomous organization called "The DAO" were securities. He has also swatted aside the industry's pleas for a comprehensive regulatory framework for crypto, claiming that "it already exists" in the form of the U.S. securities regulatory system that stretches back to the 1930s. At a fireside chat at NYU's law school earlier this month, he testily said, "Just because people don't like the law doesn't mean there's not law. You don't get to choose."

Come in and register

Gensler's oft-repeated "come in and register" refrain has become something of a joke within the crypto industry. Companies including Coinbase and Robinhood have said they tried to register as broker-dealers and were turned away. (It is worth noting that a few companies, including controversial firm Prometheum, have successfully registered as crypto broker-dealers with the SEC.)

Chelsea Pizzola, counsel for DRW, called the company's rebuffed attempts to register its crypto broker-dealer Cumberland Securities LLC with FINRA (which also plays a role overseeing U.S. markets) "very frustrating," adding: "We're not the only ones out here saying we tried to register and [who] acquired a broker-dealer, tried for years to use it … tried in good faith to engage with the SEC trading and markets staff."

There is some evidence that Cumberland DRW would have registered with the SEC if such a path were available. In June, the company received a highly coveted but hard-to-get BitLicense from the New York Department of Financial Services. NYDFS is known to be an exacting regulator and getting a BitLicense takes, on average, three years. But compared to Cumberland's experience attempting to register with the SEC, NYDFS seemed flexible in its approach to crypto regulation.

"As we were going through the process with [NY]DFS … we were also trying to engage with FINRA, trying to engage with the SEC to use our registered broker-dealer," Pizzola recounted. "We were getting so much more traction with [NY]DFS. It's a long and complicated process, but we at least felt like we were making progress, moving forward and weren't being stonewalled."

Slowing evolution

Though not registered with the SEC as a broker-dealer, Cumberland DRW is a regulated entity. It's been a leading liquidity provider to the crypto industry since its inception in 2014. And, due to parent company DRW's TradFi pedigree, it has served as a self-described bridge from crypto to the traditional financial world.

Wilson speculated that it's possible the SEC enforcement action could be a way to slow down the evolution of crypto.

"There are some people in government who believe that it's best that government has complete control," Wilson said. "And I think that crypto, as a decentralizing technology, threatens that, and if you want to slow that down, then certainly going after the TradFi–crypto bridge would be a way of doing that."

Wilson added that some lawmakers and regulators like Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) are antagonistic toward crypto because they "really believe in the power of the state," which crypto undermines.

"If that's your worldview – that the world is better off with the government having much more control – then anything you can do to slow down the progress of crypto is making the world a better place," Wilson said. "And if you have to do it in a way that's a little bit unfair to market participants, well, you're still making the world a better place."

Throwing down the gauntlet

Wilson and his company are ready for another fight against a Gensler-led regulatory agency.

In a statement posted to X (formerly Twitter) on Oct. 10, a spokesperson for the firm wrote: "We have proven before our firm's willingness to defend ourselves against overzealous regulators wielding their power in ways that harm rather than benefit the market. … We are ready to defend ourselves again."

Wilson told CoinDesk that the best-case outcome for Cumberland DRW is a dismissal akin to the one he received in 2018.

"This is such a Kafka-esque situation. I'm hopeful that the courts will see just how ludicrous this is and we'll straighten things out," he said with a laugh. "The shortest, fastest, easiest outcome would be if the judge just dismisses it."

But beyond a dismissal, Wilson and Pizzola said their hope for the case is that it will lead to clarity for Cumberland DRW and other market participants.

"We are good actors. We just want people like us to be able to innovate and engage productively," Pizzola said. "We just don't see the rationale for this kind of destructive engagement."

Wilson said beating the CFTC cost DRW a lot of money – money that the firm, as one of the nation's largest trading firms, could afford. The SEC kerfuffle has already cost DRW a lot, he said.

"I'm hopeful the courts will see just how ludicrous this is, and we'll straighten things out," Wilson said. "But it's really unfortunate. In the CFTC case, there were a lot of our resources wasted and taxpayers\.' Now with the SEC, a tremendous amount of taxpayer resources are wasted on these cases. Obviously, there were people who did bad things in crypto and the SEC should go after these people."

But in the case of DRW and others like Coinbase, "There was no path to registration, and the SEC said 'you failed to register.'"

coindesk.com

coindesk.com