The Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) Project Atlas report offers yet another indication that the worlds of crypto and traditional finance may be converging.

On the surface, this proof-of-concept project backed by some of Europe’s biggest central banks — like German central bank Deutsche Bundesbank and Dutch central bank De Nederlandsche Bank — seems modest enough: securing more crypto-related data, like cross-border Bitcoin ($BTC) flows.

But the mere fact that these giants of the incumbent financial order now want such information suggests that crypto assets and decentralized finance (DeFi) applications are becoming, in the report’s words, “part of an emerging financial ecosystem that spans the globe.”

BIS, a bank for central banks, and its partners still have some serious concerns about this new ecosystem, including its “lack of transparency.” For instance, it’s still hard to find seemingly simple things, like the countries where crypto exchanges are domiciled.

And then, there are the abiding potential risks to financial stability presented by these new financial assets. Indeed, in the introduction of the 40-page report, published in early October, BIS references how recent crypto failures — such as the recent theft of $61 million from Curve Finance’s pools — “exposed vulnerabilities across DeFi projects.” Moreover:

“The crash of the Terra (Luna) protocol’s algorithmic stablecoin in a downward spiral and the bankruptcy of centralised crypto exchange FTX also highlight the pitfalls of unregulated markets.”

Overall, this seemingly innocuous report raises some knotty questions. Does crypto have a macro data problem? Why are cross-border flows so difficult to discern? Is there an easy solution to this opaqueness?

Finally, assuming there is a problem, wouldn’t it behoove the industry to meet the central banks at least halfway in supplying some answers?

Is crypto data really lacking?

“It’s a valid concern,” Clemens Graf von Luckner, a former World Bank economist now conducting foreign portfolio investment research for the International Monetary Fund, told Cointelegraph.

Central banks generally want to know what assets their residents hold in other parts of the world. Large amounts of overseas assets can be a buffer in times of financial stress.

So, central banks want to know how much crypto is going out of their country and for what purpose. “Foreign assets can be handy,” said von Luckner. A large stock of crypto savings abroad could be seen as a positive by central banks worried about systemic safety and soundness. In times of crisis, a country may get by financially — at least for a period — if its citizens have high overseas holdings, von Luckner suggested.

Yet the decentralized nature of cryptocurrencies, the pseudonymity of its users, and the global distribution of transactions make it more difficult for central banks — or anyone else — to gather data, Stephan Meyer, co-founder and chief legal officer at Obligate, told Cointelegraph, adding:

“The tricky thing with crypto is that the market structure is significantly flatter — and sometimes fully peer-to-peer. The usual pyramid structure where information flows up from banks to central banks to BIS does not exist.”

But why now? Bitcoin has been around since 2009, after all. Why are European bankers suddenly interested in cross-border $BTC flows at this moment in time?

The short answer is that crypto volumes weren’t large enough earlier to merit a central banker’s attention, said von Luckner. Today, crypto is a $1 trillion industry.

Moreover, the banks recognize the “tangible influence these [new assets] can exert on the monetary aspects of fiat currencies,” Jacob Joseph, research analyst at crypto analytics firm CCData, told Cointelegraph.

Recent: Token adoption grows as real-world assets move on-chain

Meyer, on the other hand, assumed “rather that the emergence of stablecoins led to an increased demand for gathering payment data.”

Still, it’s complicated. Many transactions take place outside of regulated gateways, said Meyer. When regulated gateways do exist, they usually aren’t banks but “less-regulated exchanges, payment service providers, or other Anti-Money Laundering-regulated financial intermediaries.” He added:

“The usual central actors existing in the fiat world — e.g., the operators of the SWIFT network as well as the interbank settlement systems — do not exist in crypto.”

What is to be done?

Central banks are currently getting their crypto data from private analytic firms like Chainalysis, but even this isn’t entirely satisfactory, noted von Luckner. An analytics firm can follow Bitcoin flows from Vietnam to Australia, for example; but if the Australian-based exchange that receives a $BTC transaction also has a New Zealand node, how does the central bank know if this $BTC is ultimately staying in Australia or moving on to New Zealand?

There seems to be no simple answer at present. Meyer, for one, hopes that the central banks, the BIS and others will be able to gather data withoutintroducing new regulatory reporting requirements.

There’s some reason to believe this could happen, including proliferating numbers of chain tracking tools, the fact that some large crypto exchanges are already disclosing more data voluntarily, and the growing recognition that most crypto transitions are pseudonymous, not entirely anonymous, said Meyer.

Would it help if crypto exchanges were more proactive, trying harder to provide central banks with the data they require?

“It would help a lot,” answered von Luckner. If exchanges were to provide via an API some basic guidance — such as “people from this country bought and sold this much crypto, but the net was not so much” — that “would give central banks a lot more confidence.”

“Presenting regulators with clear, insightful data is beneficial for the development of reasonable regulatory frameworks,” agreed Joseph. He noted that analytics firms like Chainalysis and Elliptic already share “vital on-chain data” with regulatory entities. “This collaborative approach between crypto companies and regulators has been effective and will likely continue to be crucial in navigating the regulatory landscape.”

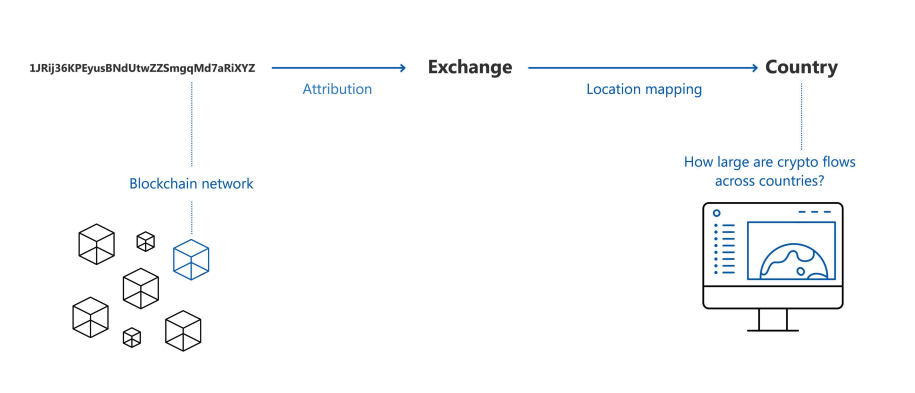

As part of a first proof-of-concept, Project Atlas derived crypto-asset flows across geographical locations. It looked at Bitcoin transactions from crypto exchanges “along with the location of those exchanges, as a proxy for cross-border capital flows.” Among the difficulties cited:

“The country location is not always discernible for crypto exchanges, and attribution data are naturally incomplete and possibly not perfectly accurate.”

So, for starters, perhaps crypto exchanges could reveal a home country address?

“There are different factors that drive this opacity,” von Luckner told Cointelegraph. Part of it is the crypto ethos, the notion that it’s a universal, borderless, decentralized protocol — even as many of its largest exchanges and protocols are owned by a relatively small cohort of individuals. But even these centralized exchanges often prefer to present themselves as decentralized enterprises.

This opacity may also be driven by strictly business interests, such as minimizing taxes, added von Luckner. An exchange may make most of their profits in Germany but want to pay taxes in Ireland, where tax rates are lower, for example.

That said, “It’s not in the industry’s interests,” at least in the longer term, because “it risks crypto being banned altogether,” said von Luckner. It’s just human nature. What people — i.e., regulators — don’t understand, they want to go away, he argued.

Moreover, the average Bitcoin or crypto user doesn’t really require a system perfectly decentralized with total anonymity, von Luckner added. “Otherwise, everyone would use Monero” or some other privacy coin for their transactions. Most just want a faster, cheaper, safer way of conducting financial transactions.

Is Europe overregulated?

There is also the possibility that this focus on cross-border crypto flows and macro data is just a European fixation, not a global problem. Some believe that Europe is already over-regulated, especially at the startup level. Maybe this is just another example?

While there are concerns that the European regulations in the past have stifled innovations, acknowledged Joseph, recent advancements, such as MiCA, have been welcomed by large parts of the crypto industry:

“The introduction of clear regulatory frameworks, something the industry has long sought, represents a significant step forward by Europe.”

Indeed, there has been an uptick in the number of crypto companies moving to Europe as a result of the developments around MiCA, Joseph said.

Meyer, for his part, is based in Switzerland, which is part of Europe, though not the European Union. He told Cointelegraph that Europe does “an excellent job of creating regulatory clarity, which is the most decisive factor for business certainty. By far, the worst a jurisdiction can do is to have either no or unclear rules. Nothing hinders innovation more.”

Does crypto need to be integrated?

In sum, a few things seem clear. First, European central banks are clearly worried. “Regulators are becoming increasingly apprehensive about the scale of crypto markets and their integration with traditional finance,” notes the report.

Second, cryptocurrencies have achieved a threshold of sorts, becoming important enough that major regulators around the world want to learn more about them.

“The more dynamic an industry is – and the crypto industry is extremely dynamic — the bigger the knowledge gap between the market and the (central) banks,” noted Meyer. So, this initiative on the part of BIS “seems reasonable, even if it might be to a certain degree also an educational purpose project of BIS and the contributing central banks.”

Magazine: Beyond crypto: Zero-knowledge proofs show potential from voting to finance

Third, it’s probably too early to say whether European central banks are ready to accept Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies without conditions. Still, it seems clear “that cryptocurrency has evolved and now demands attention, monitoring, and regulation, indicating its [crypto’s] presence in the wider financial ecosystem,” said Joseph.

Finally, the crypto industry might want to think seriously about supplying global regulators with the sort of macro data they require — in order to become fully integrated into the incumbent financial system. “The only way for it [crypto] to survive is to be integrated,” von Luckner noted. Otherwise, it may continue to exist, but only on the economic fringes.

cointelegraph.com

cointelegraph.com